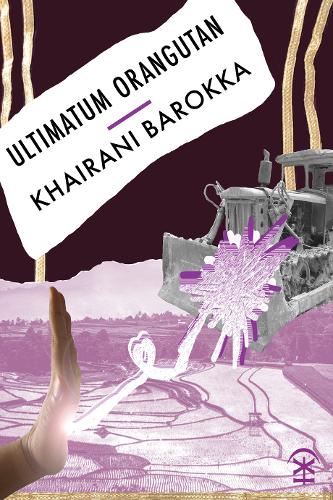

Ultimatum Orangutan, by Khairani Barokka. Published by Nine Arches Press, 2021. Available for purchase here.

Ultimatum Orangutan, by Khairani Barokka. Published by Nine Arches Press, 2021. Available for purchase here.

‘In actively shaping the territories where colonizers invaded, they refused to see what was in front of them; instead forcing a landscape, climate, flora, and fauna into an idealized version of the world modelled on sameness and replication of the homeland.’

Zoe Todd and Heather Davis, ‘On the Importance of a Date, or, Decolonizing the Anthropocene‘

‘In a time during which it is necessary to ask what structures must be dismantled in order for all peoples to live freely and well, thoughts about what will need to be abolished come in tandem with those asking what we will need to learn to grow.’

Victoria Adukwei Bulley, ‘What We Know, What We Grow at the End of the World’, In the Garden: Essays on Nature and Growing

‘The duende […] won’t appear if it can’t see the possibility of death, if it doesn’t know it can haunt death’s house, if it’s not certain to shake those branches we all carry, that do not bring, can never bring, consolation.’

Federico García Lorca, Theory and Play of the Duende

* * *

If there’s one thing Khairani Barokka’s poetry tells us, it’s that to know the present, we must understand the past. With that in mind, Okka’s1 Indigenous Species (Tilted Axis, 2016) is the perfect place to begin to think about her second full-length collection, Ultimatum Orangutan (Nine Arches, 2021). Indigenous Species is a single long poem, but what carries the reader’s eye is the collage art that surrounds the words on every page; the visual and the textual seem to hold equal esteem. Okka ties the poem, which sprang out of a spoken word performance about violence against Indonesia’s land, air and water, to a powerful central symbol: a multicoloured, glitchy and abstracted river. The river is a frenetic blend of bright reds, blues and purples, composed of traditional Dayak cloth patterns and small arrows pointing from left to right across each page, sweeping the reader along in its wake. Nothing about it feels natural, and there is a sickly anxiety about it, a highly energetic wrongness. Around the middle of the book, the river meets a smoking industrial plant, and rapidly loses its integrity, morphing into a colonial map of Indonesia, cosmetics, a tv set, before acting as the book’s last, furious image: the river turning backward against the reader’s progress in something like a tidal wave, something like wildfire, with a black, oily stain at its heart.

Katy Lewis Hood’s excellent essay on the book is essential reading, not just for its close and generous analysis of Indigenous Species, but as a solid foundation for approaching Okka’s work since then, exploring both the poet’s nuanced political critiques (of capitalism, colonialism, and euro-centric attitudes within feminism and environmentalism) and her aesthetic practice. Of the latter, Lewis Hood notes how Okka seems unhindered by arbitrary borders of genre – this is poetry, collage, storytelling, research; it is art first, let taxonomy take care of itself – how her work honours traditions that do not hold the book as the absolute literary artefact, and thinks deeply about what formal possibilities are opened by pursuing, aesthetically, accessibility for all bodyminds. Indigenous Species makes unignorable a fact that is still too often glossed over in the anglosphere: that (disabled) indigenous writers, artists and activists have centuries of experience fighting the kinds of crises to which the global north is only lately awakening.

* * *

Ultimatum Orangutan is Okka’s second full collection, after 2017’s Rope (also Nine Arches), but it feels intimately linked to the experiments that made Indigenous Species so unique. Like Rope, it is composed of individual lyrics; a studio rather than a concept album. The ease with which it shifts focus between the globally systemic and the personal makes both feel interwoven; the imagination in Ultimatum Orangutan is a political tool. It also feels a degree of magnitude more intense, more finely tuned than her previous work, like Okka has pushed politeness far down the poems’ list of priorities and is relishing the space they make for play between rage and grief, their wild dreamlife and earthy embodiment. Reading a lot of these poems back-to-back is almost dizzying, a sensory overload like staring at a surrealist painting, or a meal with many rich flavours. In its looser, more conversational modes it feels akin to Nisha Ramayya’s poetic research in States of the Body Produced by Love; in its moments of lyric brilliance around love, land, dreams and bodies, it feels like very little else published in this country: the closest touchstone I could think of is Natalie Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem, in both books’ celebration of the intimately physical alongside the eternal.

Ultimatum Orangutan’s opening piece, ‘Hello, Sequelae’ – ‘sequela’ being a medical term for a chronic complication of an acute condition – addresses the reader directly:

Because another storm is humming,

you squat by a creek, chin out.

Tease the fringes of river intoxicant,

thumb and forefinger dunked in the wet,

breathing air that makes you a statistic.

Hard to miss the callback to Indigenous Species in ‘river intoxicant’, or how the poem frames the body (your body) as an interface, an instinctive point at which the world makes itself known. The words ‘intoxicant’ and ‘statistic’, meanwhile, feel discordant here, as if they have been collaged from a different text. Each stanza in ‘Hello, Sequelae’ forms its own dramatic movement; more so than any other poem in Ultimatum Orangutan, this poem feels ceremonial, an action whose artifice is part of its purpose. Movement two continues to give ‘you’ directions, to ‘face what the minnow knows / what stoic ducks understand’, while the third movement gets fascinatingly weird:

A falling outwards of equilibrium

hunts a sore chest, senses insects

leaving the grounds where you make

fast cover, temporary, walls

already so pale, so fading, ivory

as the full teeth of ghosts.

Where the previous stanzas were immersed in the physical, here the poem digs into senses we don’t quite have names for: raised hairs on the neck that detect of the movement of insects; the ability to envision the literally concrete as something less material than the jaws of the dead. (That last line, ‘ivory / as the full teeth of ghosts’, is what first made me think of Lorca: more on that later.) ‘Hello, Sequelae’ concludes:

you have always been so open

to skin-piercing things, there is no

safe house. In your hands

is how to seed earth.

You have always known how

to tell time by sky.

Simple, right? Yet this is a thought that undermines one of the most basic assumptions of imperialism, that our alienation from the natural world, from each other, and from the needs and limitations of our bodies, makes us advanced, enlightened, safe. It follows, then, that all societies and bodyminds that do not experience this enclosure are regressive and in need of saving, to be raised out of relation with nature. The ‘sequelae’, then, the acute condition of the poem’s title, does not belong to a bodymind deemed dysfunctional by Western medicine – Okka notes in an interview how Dutch colonial doctors forced unwanted medical practices onto a Javanese culture that honoured disabled deities – but of the systems of knowledge that compel the body into relations it cannot sustain.

The other beautiful trick the poem pulls only occurred to me after multiple readings. First time round, I didn’t like the phrase ‘stoic ducks’. It felt neatly comic, but a little off-key; the book is called Ultimatum Orangutan, the cover has an image of West Sumatra, and this is the first poem, so I assumed the poem was set in Indonesia. What are ducks doing here? But looking closer (and googling ‘do ducks live in Indonesia?’), there’s nothing in the poem to say whether this is West Sumatra or, say, Scotland, nothing I couldn’t find in a twenty-minute walk from my flat: the ducks’ un-poemy-ness jarred me out of the safe distance of an imagined elsewhere. The book is in my hands, and, in the poem’s pointed use of the second person, it wants to make clear that I am the one ‘open / to skin-piercing things’, that capital’s ‘safe house’ will not save me. The calm determination of the poem is impressive; that Ultimatum Orangutan sustains this energy through so many of its poems is what makes it such a remarkable achievement.

* * *

Ultimatum Orangutan speaks the language of the body with finesse and often delightful frankness, from small, intimate, eloquent gestures to wild and messy expressions of love and desire. ‘pylons’ belongs to the former category, beginning as a sad, quiet rumination on loss and the body of an ecosystem: ‘i am / infested with burnt and breaking pylons. / a shock to the limbic system of a / rainforest, i am fracked nervous systems.’ Though the imagery is of destruction and violence, something in the texture of these lines feels gentle, almost resigned, as if the speaking voice has lost their appetite for anything but the plainest rhetoric. So, when the poem turns in its closing lines, it hits like a truck:

i am the palms of your mother

in the dead of night,

when all rushes to extinction,

and constellations swarm your body,

reminding you of what is here still.

I hear that ‘still’ both as ‘despite everything’ and as ‘unmoving/quiet/peaceful’; the ‘palms’ both as the mother’s body and the tree whose industrial harvesting haunts Indigenous Species. The collection draws so much strength from these tableaux in the small hours, when the daily machinery pauses, the imagination takes hold, and an extraordinary gesture like this one bubbles up from the mind’s deep places. The doom spiral has not been defeated, by any means, but the poem gives centre stage to these reassuring, loving hands, the possibility, pace Lorca, of consolation in the face of death.

This feels like Okka’s skill as a collagist translated into text: many of Ultimatum Orangutan’s finest pieces are composed of disparate images, set alongside each other in a suggestion of narrative, or argument, progressing as often by dream logic as the waking kind. In ‘pain speaks to okka’, surrealism is again the vehicle for the poem’s thinking on the body and its slippages, one that seems to take debilitating pain as a form of creativity, for drawing wry and fluid relations between the body and the sensory world. It begins:

in bent memory, the wind pushed the blue of a moon

through all the still windows in that submarine apartment, […]

laid your wave-kissed nightclothes on the ocean floor

The phrase ‘bent memory’ is such a beautifully idiosyncratic expression, that feeling of the conscious mind’s sudden loss of linear, logical thought. I had Lorca on my mind when reading Ultimatum Orangutan, and this is the poem that connected the dots: it feels like a distant relative of ‘Romance Somnámbulo’, Okka’s palette of blues and blacks in place of Lorca’s greens and silvers. What sets it apart is Okka’s dry and often self-deprecating humour, the way the poem simultaneously despairs of and glorifies the ways the body misfires and makes itself unignorable:

underwater-set acidic torture den of the next

several years the non-psychosomatic, nonetheless

stress-fakakked-at-inception wet thing.

yes pain is wet i am the ambush maven,

the s-&-m party the hurricane-thrown stars

of an esoteric ninja sadist,

current of firepit water, is that who god is.

I couldn’t find a standard definition of ‘fakakked’, but I understand it. The grammar of that last line makes no logical sense, but I (maybe) understand its transliteration of a racing, sleepless mind grappling with an elusive thought. ‘pain speaks to okka’ is, as its title suggests, an intimate retelling of an internal conversation, and its relation of the realities of embodiment is careful and generously legible; that it is also a vivid and daring sense-scape is what has kept it on my mind for weeks.

* * *

It’s difficult to move away from the fact that, as the title suggests, Ultimatum Orangutan refuses to turn away from endings, both small and very, very large. A four-part poem titled ‘Terjaga’ – the final part reveals to a non-Indonesian speaker that the word means both ‘awake’ and ‘protected’ – forms a kind of backbone, or touchstone, or, like Indigenous Species, an organising symbol for the collection, and pushes back against the idea of the crisis being new, or unforeseeable, with a refrain that changes only slightly from one part to the next:

any mind that carries singular future apocalypse, without mass current and past apocalypses in mind – colonial, linear time – is a ______

‘Future apocalypse’ becomes, in the second poem, ‘future genocide’, ‘future resistance’ in the third, and finally ‘future salvation’. The blank underscore appears each time, a space I hesitate to fill too easily: I suspect that mind is still, despite good intentions, my own. The linearity of ‘colonial time’, the notion of constant and unbroken ‘progress’, is framed as delusional, a position that can only be maintained by a forceful alienation from the experiences of the colonised. And the most effective counter to this mass atomisation, the book argues time and time again, is locating oneself in relation to others. Everywhere in the collection, from its cultural/political critiques in ‘Eropa’ and ‘mediterranean lyric’, to the title poem’s lyric essay on the ‘visualchimp language’ of pop culture, to the dozen-or-more poems on family, elders and life in community, Ultimatum Orangutan keeps itself afloat, keeps despair at bay, by knowing its history, and through it a deep and powerful sense of the present. The river as connective tissue in Indigenous Species, the eponymous images of ligature in Rope, and the hands and inheritances here; the heart of Okka’s poetry is this situating of the self among others, human and non-human, living and non-living.

‘on lying down, apocalyptic’ holds this devastating tension between the encroaching dread of collapse and crisis, and a vision of a viable, desirable future:

and in this version of the end / i am surrounded by nieces and nephews / brachial weaponed, most standing / against the wave of threatening deathknell / and i will be glorifying also with those who choose / not to stand but to rest with me prone […] to save life against terrors by way / of circulatory relief

Sometimes, Okka argues, survival looks like resting with those who can no longer stand. Ultimatum Orangutan is a powerful, challenging, enriching book, one that has little time for the polite delusions that often comprise poetic writing on nature in these islands, and neither offers nor accepts simple answers to complex and deeply knotted questions. It may well be its refusal to soften its political message or dilute its formal ambitions in the name of the reader’s comfort or the poet’s ‘respectability’ that make its passion so sustaining, that make its occasional discordant notes – a few poems, like ‘abecedarian for other alphabets’, or ‘Fence and Repetition: A History of Climate Change’ don’t quite carry the same weight of their neighbours, despite their robust politics – still feel purposeful. And everywhere in the book are devastating lines I’ll carry with me for a long time: ‘the woods / as a set of conquerable names’ (‘remaining outpost’); ‘like when we know a truth to be true because our body feels like it has returned to its right place’ (‘Terjaga I’); ‘but if I knew the answer for where on this tiny / orb we are meant to find constancy of grace / neverending, I’d go off and sing, self-satisfied.’ (‘Horizon’). Out of the jaws of death and collapse, Ultimatum Orangutan is generous with its visions, unflinching in its critiques, and always, as in the image of a mother’s hand in ‘pylons’, reminding us of what is here, still.

1 This essay refers to the poet as ‘Okka’ in line with Indonesian naming conventions as per her essay on the topic.

Dave Coates is a poetry critic based in Edinburgh. Most of his writing can be found on davepoems.wordpress.com.